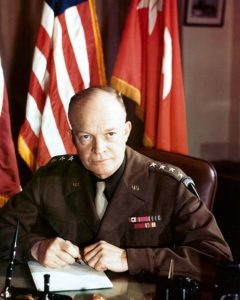

Skeptics of Agile—myself among them—are indebted to Dwight (“Ike”) Eisenhower, U.S. president from 1953–61. “In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence… by the military industrial complex,” he said that last year. “The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”1 From this was coined the term, “Agile Industrial Complex.”2 It refers to associations, consultants, and especially, consulting/staffing firms, who gain “unwarranted influence” by telling executives what they want to hear about agility—even subverting the Agile principles if that’s what it takes to make the sale.

I was intrigued, then, to come across a book on Ike’s leadership philosophy, having already read his autobiography. His methods are not what you might expect from the commander-in-chief of Allied forces during World War II. Themes you often hear in modern writing about agile management appear throughout How Ike Led: The Principles behind Eisenhower’s Biggest Decision. I have an “advance reader” copy, which forbids directly quoting the author, his granddaughter Susan, a policy and leadership consultant. I’ll summarize instead.

A major theme is fair and equal treatment of employees, which Ike believed was critical to morale:

- A general tried to impress a lady by hinting at the date of D-Day, the invasion of Normandy in 1944. Despite his being a friend and military academy classmate, Ike removed and demoted him. The general appealed, and was told his previous good record was the only reason he wasn’t court-martialed!

- After Gen. George Patton slapped two soldiers probably suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, Ike made him apologize to them and all of his troops. He also passed over Patton for command of the D-Day invasion.

- Knowing that a high percentage of the paratroopers sent behind the lines during D-Day would die, Ike went to the takeoff point, talked with many of the men, and waited on the tarmac as they left.

- After the war, he was the first president of Columbia University to hold meetings not only with faculty, but also with line staff like gardeners. He emphasized the importance of every job, and invited everyone to greet him as “Ike” in passing.

Another theme was taking ethical stands that might get him in trouble. As U.S. president, he vetoed a bill he agreed with in principle because of what he viewed as crooked lobbying that led to its passage: One business executive was quoted in newspapers as saying a senator was “in his pocket.” And in a sign of fairness that seems unbelievable in today’s political environment, during his 1956 reelection campaign, he nominated a Democrat for the Supreme Court. Ike was a Republican, but said Democrats had a right to friends on the court.

Ike was also, in effect, an early proponent of evidence-based management and getting multiple perspectives. Susan Eisenhower says he insisted on following where the facts led. Addressing the American Bar Association in 1949, he said, “The frightened, the defeated, the coward and the knave run to the flanks… under the cover of slogans, false formulas and appeals to passion—a welcome sight to an alert enemy.”

To determine the best approach to military spending related to the Soviet Union, Ike convened what was called the “Solarium Project.” Three teams researched and then argued for more, less, or the same spending, each answering 21 questions Ike assigned. The groups presented their findings to a large, cross-functional audience. After an audience debate, he endorsed a combination of the first two positions.

Ike embraced change, having no patience for people who refused to amend their opinions when circumstances changed. He also encouraged debate with him and across departments, the book says.

Finally, he delegated decision-making downward, understanding that the top manager cannot supervise operations on a daily basis. Instead he assigned objectives to groups and distributed the needed resources. Ike succeeded at war, despite having no combat experience, because of his focus on strategic skills. He left the tactical decisions to the tacticians.

All that said, Ike was not quite the stick-in-the-mud he might seem. As a cadet at the U.S. Military Academy, he got in trouble for numerous irreverent acts. When told once to appear for disciplining wearing the academy’s formal dress coat, that’s the only thing he wore!

One of the most powerful people of the 20th Century disciplined his friends when needed; chose ethics over his supporters’ wishes; showered personal attention on workers; recognized his limits; invited contrary input; and followed facts and evidence to their logical conclusion. By doing so, he led a massive military machine to victory, and is considered one of America’s most effective presidents. I wish more business leaders, and politicians of all stripes, would follow his agile example.

Source: Eisenhower, Susan, How Ike Led: The Principles behind Eisenhower’s Biggest Decision (Advance Reader Copy), (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2020).

2 I came up with the term independently based on Ike’s speech, but did not publish it until 2017. Someone else, I later found, had done so in 2014, so I cannot claim to have coined it!